This is a continuation of my interview with Ontario artist, Leigh Cooney.

Question: Why did you decide to paint, as opposed to doing another kind of creative art? How does painting make you feel?

Answer: I’m a very complicated person. I was born with what I consider to be a broken brain and things have always just kind of rattled around up there. I tend to think things through until they’re so much more complicated than necessary, and I make life more difficult than it needs to be. So any chance I get to make things simpler, I take it. When it comes to painting I find it almost therapeutic to keep my materials to a minimum. So rather than being an adventurous artist trying out a lot of different materials and mediums, I stick to 5 tubes of paint and two or three brushes. I mix all my colours from the primaries and I don’t bother trying to make exactly the same colour twice.

Question: Were you trying to achieve a certain outcome or look, or were you just experimenting?

Answer: I did a couple of paintings in high-school when I was first introduced to oil paint and yes, I was trying to achieve something specific. When I realized I couldn’t accomplish this after 3.5 paintings I gave up all forms of art. I had no patience for learning, and I wanted to be “good” right away. Not counting those, I sat down in front of my first canvas when I was 27 with a renewed idea of what made a “good” painting. When I was a teenager I thought every artist had to paint like the masters or they clearly had no talent. It was my discovery of Jean Michel Basquiat (and Outsider art around the same time) that turned my life around slowly. I realized that there were forms of artistic expression that were an acquired taste, and their riches

weren’t always handed to you, they often required repeated viewings.

So I sat down at that canvas and I promised myself I would go against every pedantic impulse that came naturally to me and I would start and finish my first painting that afternoon. I wouldn’t try to adjust anything or envision how it would turn out. My very first painting from that time period was a socio-political one involving sex scandals and the nature of celibacy. With my next few paintings I

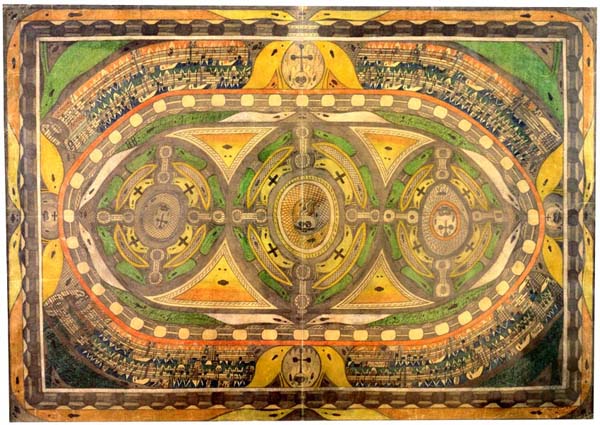

decided to attempt to do with oil paint and canvas what I had failed to do for the past 27 years with mere words, I would show people visually what was happening in my head. My brain has always been feverish, and my thoughts come to me either muddled and out of order or tripping over themselves to get out first. It was only three years later that I decided to approach a doctor and do some tests. It turns out I’ve suffered for the past 30 years from a serious case of (the incredibly misunderstood) Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder, or ADHD.

Question: Did you show your work to anyone? What did they think about it? Did it matter to you if they didn’t like it?

Answer: As I mentioned, I painted three and a half paintings in high school before I quit. I hung three of those in a local used clothing

store at the advice of a friend and I sold my first painting that week for $50. I was 19. To me this was incredible, but not incredible enough to dispel my doubts about my skills. When I painted again at 27, I showed a few friends over drinks. I don’t think they liked them but they were too polite to say. A few months later however I uploaded them to Facebook (which was still brand new) and started sharing them on FB pages that dealt with self-taught art. I made my first real fans that way.

Question: Has your style changed over the years?

Oh yes. At first I was trying to paint freely the way Basquiat did, as I felt that was most reflective of my personality, but I just couldn’t fight the need to tighten things up. Eventually I decided to settle on something in the middle. I don’t want to paint realist paintings, but I’ve realized that painting a lot of detail is conversely very therapeutic for me. My head might be full of firecrackers, but when I become engrossed in a painting I stop thinking about anything else and for a few hours my body becomes less tense and I become detached from the outside world that I feel so uncomfortable in. The firecrackers become more like popcorn, and that’s okay. I still only paint as much detail as I feel will benefit the painting. Once I start adding in additional details, the fever in my brain starts to creep back in and I find it difficult to finish the work.

Joseph Hofer

Joseph Hofer