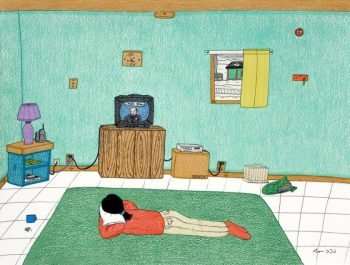

Annie Pootoogook, Junior Rangers (2006)

Annie Pootoogook, Junior Rangers (2006)

I am often asked about Indigenous art when I am outside Canada, as many equate it with outsider art, perhaps because it is foreign and exotic to their eyes. They say they have not seen anything like it before, especially art from Canada’s Inuit communities. But novelty is not synonymous with outsider art, and it would be unfortunate if such views reflected outdated notions of so-called primitive art. This topic is explored my book, Outsider Art of Canada, but here is a brief synopsis.

The move to apply the outsider art label to Canadian Indigenous art is puzzling, as the label is not attached to the work of Indigenous artists in other countries. The artwork of Native Americans, Indigenous Australian peoples, or New Zealand Māori, for instance, is not considered outside of anything — it is respected as art in its own right. Yet some seek to place Canada’s Indigenous artists in the outsider art category, arguing that the effects of colonialism are directly responsible for the marginalized status of their people. While the same argument can be made with respect to Indigenous peoples in other countries, there has been no move to attach the outsider label to their artwork. While he trauma of Canada’s Indigenous population through centuries of oppression is an undisputed fact, the artwork of a marginalized population ≠ outsider art. In fact, the work of traditional Canadian Indigenous artists reflects styles particular to each community while other artists, like Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun and Ken Monkman, have moved into the contemporary art world.

Contemporary Inuit drawings (of the past 20 – 25 years) certainly offer a fresh perspective on life in Canada’s north and the art is admired by outsider art collectors, particularly those who embrace folk and naïve art as part of the outsider art genre. But the drawings are not part of traditional Inuit culture; they are a new art form with a remarkable history. In the 1950s, the government of Canada relocated the nomadic Inuit population to permanent community settlements. With diminished means to support themselves, Japanese printmaking was introduced by Qallunaat (non-Inuit) to the Inuit community of Kinngait, Nunavut as a way to boost the local economy. While the prints depart from conventional Inuit imagery, that does not mean they belong in the outsider art category. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that their work has matured beyond the borders of more traditional first and second generation Inuit art. Today, production of prints is a significant source of income for Arctic communities and the prospect of financial independence is the impetus for many Inuit artists. In contrast, outsider artists are compelled to create for personal reasons; financial reward and recognition is not what drives them to create art.