Day 1 of writing was very productive. It was definitely the right decision to take myself away from work-work and unnecessary home chores. Things are good, despite the heavy rains. I decided to go out this morning to buy fire logs instead of chopping down a tree in the forest. I lost my glasses in the process. I am SURE they are somewhere in the gas station, although the staff there denies this. Meanwhile, I’m squinting a lot.

Day 1 of writing was very productive. It was definitely the right decision to take myself away from work-work and unnecessary home chores. Things are good, despite the heavy rains. I decided to go out this morning to buy fire logs instead of chopping down a tree in the forest. I lost my glasses in the process. I am SURE they are somewhere in the gas station, although the staff there denies this. Meanwhile, I’m squinting a lot.

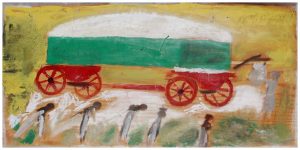

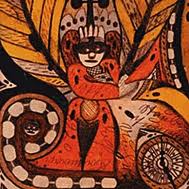

Here is a summary of my writing on “the myth of the mad genius” today. It’s where (I believe) the tangled web of what constitutes outsider art began. More – way more – will follow, including what happened when we changed the terminology from art brut to outsider art.

The concept of the mad genius is deeply embedded in our culture. In reinforcing the stereotype that a life of psychological torture is the price one must pay for creative genius, it trivializes the reality of mental illness and glamorizes the profound truths it can apparently reveal. Nevertheless, the myth has persisted for centuries, despite a dearth of scientific evidence that such a connection exists.

The story of art brut and its link to mental illness begins in the 19th Century. Public “lunatic asylums” were established and radical theories of the unconscious mind were endorsed by Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. More importantly in the history of art brut, the 19th century was the Age of Romanticism, when the savage was noble, the genius was mad, and the hero was a misunderstood outcast. Madness was a metaphor for freedom from the constraints of society; the madman travelled to new planes of reality and was granted special status, being free from social convention and having access to profound truths. While there had been a discussion about the mental state of creative individuals for the past few centuries, they fell short of a diagnosis of clinical insanity. Asylums, where art might be found, opened the door for the study of creativity and madness. To the Romantics, madness was both a piteous and exalted condition and a welcome reprieve from “dreaded normality”.

The story of art brut and its link to mental illness begins in the 19th Century. Public “lunatic asylums” were established and radical theories of the unconscious mind were endorsed by Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. More importantly in the history of art brut, the 19th century was the Age of Romanticism, when the savage was noble, the genius was mad, and the hero was a misunderstood outcast. Madness was a metaphor for freedom from the constraints of society; the madman travelled to new planes of reality and was granted special status, being free from social convention and having access to profound truths. While there had been a discussion about the mental state of creative individuals for the past few centuries, they fell short of a diagnosis of clinical insanity. Asylums, where art might be found, opened the door for the study of creativity and madness. To the Romantics, madness was both a piteous and exalted condition and a welcome reprieve from “dreaded normality”.

The debate about the artist as mad genius typically begins with psychiatrist and criminologist Lombroso who, in 1909, studied the work of his psychiatric patients. He concluded that genius was a type of insanity that caused people to regress to an earlier and savage stage of development; therefore, in his logic, both the madman and the genius were degenerate types. Several years later in 1911, British psychiatrist Hyslop reached the same conclusion, dismissing the “non-art” of the mentally ill as pathological and warning of its degenerate influence. It was accepted that the genius was mad, but the question remained: did the mad themselves create works of genius?

Prinzhorn, a psychiatrist (and art historian) at the University of Heidelberg, argued that his institutionalized patients’ artwork should be studied as the work of individuals, not examined for signs of mental illness. He expanded a collection of art created by his predecessor and published a book in 1922, Bildnerei der Geisteskraken (generally translated as Artistry of the Mentally Ill). He used the term “bildnerei” (image making) as opposed to “kunst” (art) to distinguish his patients’ creative output from the work of artists. Psychiatric patients, he felt, did not have the freedom, self-awareness, or skill of “sane” artists. They did, however, have the ability to see into new worlds, along with children and savages.

Prinzhorn, a psychiatrist (and art historian) at the University of Heidelberg, argued that his institutionalized patients’ artwork should be studied as the work of individuals, not examined for signs of mental illness. He expanded a collection of art created by his predecessor and published a book in 1922, Bildnerei der Geisteskraken (generally translated as Artistry of the Mentally Ill). He used the term “bildnerei” (image making) as opposed to “kunst” (art) to distinguish his patients’ creative output from the work of artists. Psychiatric patients, he felt, did not have the freedom, self-awareness, or skill of “sane” artists. They did, however, have the ability to see into new worlds, along with children and savages.

Artist Max Ernst happened to see the Prinzhorn collection and brought the book back to Paris. Extolling the liberating work of psychiatric patients who took voyages of discovery to the unconscious, the surrealists, led by André Breton, created their own “cult of insanity”. As a way to explore the unconscious mind, they studied dreams and practised automatic writing, activities they believed approximated madness because there was no logic, reason or structure.

French artist, Jean Dubuffet, was a radical member of the surrealist group. He argued against the traditions of art history, where art is studied in the context of its historical development. That art should imitate art was an anathema and such a situation should not be allowed to exist. To Dubuffet, contemporary art was like a parlour game where players must understand a secret language to appreciate the artwork. Society had unwittingly accepted the rules of the game and these rules must be challenged.

Dubuffet had a two-fold agenda: to subvert and expose the emptiness of conventional modern art and to explode the traditional solidarity between artists, critic, and public. In his view, art standards are the result of cultural conditioning and stereotyped opinions where no one dares question the value of a work. We have come to accept that only art that hangs in a museum is worthy of consideration:

… art is the monopoly of the privileged intellectual and the professional artist. … [T]he art system is sustained at the centre by a cultural ideal that is untouchable and inalterable, based as it is on the unshakeable belief in such things as our “cultural heritage”, the legacy of the past, and the fetish of the “great masterpiece” .

Dubuffet asked that we not blindly accept the status quo, but rather, embrace other kinds of art. He asked that we consider this question: what else could art be like?

Dubuffet began to collect art that he believed was unadulterated by culture and mimicked nothing; that is, art that is “raw”. Thus, the term “art brut” (raw art) was coined. Its creation was direct, uninhibited, original, and unique; the creators did not consider themselves to be artists, nor the work they produced to be art. Art brut is visual creation at its purest – a spontaneous psychic flow from brain to surface. His collection began with the work of those far removed from the commercial art world: psychiatric patients, self-taught artists, and isolated individuals.

Dubuffet began to collect art that he believed was unadulterated by culture and mimicked nothing; that is, art that is “raw”. Thus, the term “art brut” (raw art) was coined. Its creation was direct, uninhibited, original, and unique; the creators did not consider themselves to be artists, nor the work they produced to be art. Art brut is visual creation at its purest – a spontaneous psychic flow from brain to surface. His collection began with the work of those far removed from the commercial art world: psychiatric patients, self-taught artists, and isolated individuals.

Dubuffet’s initial description of art brut artists is accepted in many art circles today (a topic that will be explored later in this thesis). Art brut artists draw on their own pure, unrefined, artistic expression to create work that springs from their own obsessive need to express themselves, forcing each one to invent his or her own language and means of expression. The artists do not draw on tradition. In fact, they are quite oblivious to the notion of conveying anything to us and oblivious to the very existence of a public.

Dubuffet’s initial description of art brut artists is accepted in many art circles today (a topic that will be explored later in this thesis). Art brut artists draw on their own pure, unrefined, artistic expression to create work that springs from their own obsessive need to express themselves, forcing each one to invent his or her own language and means of expression. The artists do not draw on tradition. In fact, they are quite oblivious to the notion of conveying anything to us and oblivious to the very existence of a public.

While much of Dubuffet’s art brut collection was made up of work by patients in psychiatric institutions, he argued against the art of the insane. There was no such thing as “the art of the mad anymore than there is an art of people with sick knees” . However, he believed that “madness unburdens a person, giving him wings and helping his clairvoyance… ”.

In general, Dubuffet’s artists were isolated outcasts who created art in unconventional ways. They were unaware of being artists: they had no desire to communicate with an audience and they did not ask to be understood. They were indifferent to any social approbation or commercial gain. In essence, art brut artists were “the un-culture” of the art world. They were “ignorant of any order but their own obsession with image-making”.

In general, Dubuffet’s artists were isolated outcasts who created art in unconventional ways. They were unaware of being artists: they had no desire to communicate with an audience and they did not ask to be understood. They were indifferent to any social approbation or commercial gain. In essence, art brut artists were “the un-culture” of the art world. They were “ignorant of any order but their own obsession with image-making”.

So what of the assertion that madness fosters

artistic genius? Next blog…