My mother passed away two months ago today. Taking some personal time this morning to reflect on that.

Author Archives: kitsmediatech

The expanding boundaries of outsider art

Dubuffet’s original art brut collection was ultimately housed in the Collection de L’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland and remains there today. As Dubuffet’s collection grew, it became clear to him that some artwork did not quite “fit” into the narrowly defined category of art brut. Although the work was powerful and inventive, the artists’ contact with society and their awareness of their own work precluded their inclusion in the art brut category .

These artworks were moved to the Annex Collection, and re-named neuve invention. Dubuffet described these as “works which, though not characterized by the same radical distancing of mind as art brut, are never the less sufficiently independent of the fine-art system to constitute a challenge to the cultural institutions.

It is said that Dubuffet created a paradox he hoped to avoid. In deciding who was “in” the art brut collection he had to exclude artists whom he admired. Without intending to do so, he created a new orthodoxy of inclusion. Beginning with a subversive attitude towards art, he ended up establishing a new set of rigid criteria. Thus, in respecting the parameters of art brut, he undermined its fundamental principles and housed it in a tight box. He set up a two-tier and elitist distinction between first and second class outsiders.

Here’s where things started going sideways:

In 1972, Roger Cardinal, a professor at the University of Kent, set out to write about art brut. His publisher insisted on a catchier title, and so Outsider Art went to press. Although the term “outsider art” was not used in the text of the book, Cardinal intended it to be synonymous with art brut, and from the outset it encompassed the categories of both art brut and neuve invention.

In 1972, Roger Cardinal, a professor at the University of Kent, set out to write about art brut. His publisher insisted on a catchier title, and so Outsider Art went to press. Although the term “outsider art” was not used in the text of the book, Cardinal intended it to be synonymous with art brut, and from the outset it encompassed the categories of both art brut and neuve invention.

Cardinal defined outsider art (and art brut) as “strictly un-tutored and exists outside the normal concept of art. Not hooked up to galleries and certain expectations. It should be more or less inwards-turning and imaginative – self-contained as it were.” Although it was not Cardinal’s intention, the narrowly-defined and closely-guarded world of art brut was turned upside down. Consequently, in recent years, outsider art is an umbrella term used to describe art brut and many other artistic styles, particularly in North America. It often refers to “any artist who is untrained or with disabilities or suffering social exclusion, whatever the nature of their work”. Here is a list of new terminology that is now used in describing outsider art (or similar artwork):

- self-taught

- naïve art

- visionary

- Folk art and contemporary folk art

- Marginal art

- Art singulier (French marginal artists)

So, here we are, seven decades after Dubuffet exposed the self-serving biases of the established art world. We may have accepted the “otherness” of non-traditional art, but cannot agree whether it should be lumped into one category or distinguished by markers that reference stylistic features or the characteristics of its maker. It is called “term warfare.”

In an effort to define outsider art, some have suggested the term “art brut” should refer only to Dubuffet’s original collection in Lausanne. (I have been advised, however, that the term “art brut” is still frequently used in France.) Others, like Cardinal, have proposed a spectrum of “outsiderness” that references the position of the artist along a spectrum of psychological experience. In the USA, the term outsider art has been declared prejudicial, suggesting the artist is on the outer limits of society. Instead, the preferred term “self-taught”. Others refer to stylistic indicators. Another group points to class issues and marginalization as defining factors.

All struggle with the problems inherent in a collection of art that runs parallel to established art history and shares few common characteristics within the category itself. Cardinal himself warns that applying a set of outdated rules may result in one of two outcomes: either setting up an elitist distinction between classes of outsider artists or having the category crumble completely under the strain. He calls for a looser definition, even though it may decrease our ability to discriminate among creators and their creations.

Why does all this matter? Terminology is important because it is more than a mere descriptor; it carries a set of criteria used for classifying the artwork. Is it outsider art or not? When I began researching outsider art in Canada, I discovered there is no history or established criteria to rely on in this country. For me to introduce outsider art to Canadians, I had to understand how others in the art world defined outsider art. That has not been an easy task.

Why does all this matter? Terminology is important because it is more than a mere descriptor; it carries a set of criteria used for classifying the artwork. Is it outsider art or not? When I began researching outsider art in Canada, I discovered there is no history or established criteria to rely on in this country. For me to introduce outsider art to Canadians, I had to understand how others in the art world defined outsider art. That has not been an easy task.

The myth of the mad genius

Day 2 and all is well. I woke up to discover that some creature had been on my deck during the night. I am hoping it was not of the carnivorous species. Thankfully, no sign of bear scat.

I had to take a short break this morning to organize all the magnetic words on the fridge. They are now arranged according to basic grammatical categories: nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc. It may have taken the all the fun out puzzling through a random collection of words, but think how much faster it will be to create poetry while waiting for the kettle to boil!

(And, yes, I do realize how annoying it can be to live with me.)

Thanks to all of you who are sending me your good wishes every day. Much appreciated.

Here is a summary on today’s work on the myth of the mad genius. Please consider these blogs only as sketches of topics in my thesis – like drawings on the back of an envelope…

So what of the assertion that madness fosters artistic genius?

Although usually associated with the Age of Romanticism, madness has been connected with visionary power from the time of the ancient Greeks. Plato, for example, introduced the concept of “divine madness”, but in a very different context. Such madness was a creative inspiration delivered by the gods, more like a “muse” than a mental disorder. It is argued that Aristotle’s description of melancholia was modified to fit the “mad” stereotype by depressed writers who sought to verify that their suffering was proof of their superiority.

In the 20th Century, studies have explored the connection between mental illness and creative genius. While some research purports to confirm the connection, others dismiss any significant relationship. One vocal critic describes the dramatic presentation of mad geniuses in the media, as the “insanity hoax” presenting information as fact, not theory. She challenges the research as unscientific and anecdotal at best, and self-serving at worst:

In the 20th Century, studies have explored the connection between mental illness and creative genius. While some research purports to confirm the connection, others dismiss any significant relationship. One vocal critic describes the dramatic presentation of mad geniuses in the media, as the “insanity hoax” presenting information as fact, not theory. She challenges the research as unscientific and anecdotal at best, and self-serving at worst:

Such misunderstandings help perpetuate the mad genius idea, but the romance, the schadenfreude, the comfort, and the alibi of it are all too enjoyable to let anything shatter the myth, including science. And because this madness sells, the media will continue to hammer its connection to creativity… And the bottom line is that society may well be stuck with the idea forever, regardless of what any researchers do, or don’t do.

(Note: the image above is from one of many sites that reference the questionable research.)

There is danger in accepting the myth of the mad genius. First, we view the artist through a warped, generic lens and reduce the creative output to a product of mental illness. Second, the myth becomes a cultural truism; we are so charmed with the idea that we fail to question whether it is based in science or wishful thinking.

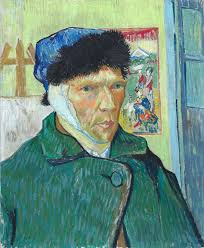

Van Gogh is the poster boy for the mad genius. Everyone knows the story of him cutting off his ear (and the self-portrait of his bandaged head). Yet all we choose to remember about him are his unique and magnificent paintings, his mood swings, and his ultimate suicide as proof of his mental illness. What we do not acknowledge are his poverty, loneliness, artistic failure, epilepsy, absinthe poisoning, and tertiary syphilis (with symptoms that mimic the mood swings and psychosis of bipolar disorder). His life circumstances alone would surely lead to grief and despair. Why must we make a posthumous diagnosis of bipolar disorder to appreciate his artwork?

Van Gogh is the poster boy for the mad genius. Everyone knows the story of him cutting off his ear (and the self-portrait of his bandaged head). Yet all we choose to remember about him are his unique and magnificent paintings, his mood swings, and his ultimate suicide as proof of his mental illness. What we do not acknowledge are his poverty, loneliness, artistic failure, epilepsy, absinthe poisoning, and tertiary syphilis (with symptoms that mimic the mood swings and psychosis of bipolar disorder). His life circumstances alone would surely lead to grief and despair. Why must we make a posthumous diagnosis of bipolar disorder to appreciate his artwork?

Mental illness is now the “must have” accessory, especially for celebrities who disclose their diagnoses of mental illness in every weekly magazine. Bi-polar disorder is the “new black.” The public has been taught that mental illness is a pre-requisite or by-product of creativity, making that celebrity unique and the condition fashionable. Children have been reported to fake mental illnesses to emulate these celebrities.

Why is this happening? It has been said that media coverage underscores the danger that accompanies creative talent, thus softening the jealousy that inevitably arises from their success. It has also been suggested that “wannabes” intentionally cultivate a wild pose to appear more brilliant than they really are, and to get a pass on the mundane responsibilities of life. As they say, any publicity is good publicity. Does all this disclosure result in stigmatization of mental illness or does it trivialize the very real difficulties of those who suffer from such illnesses?

Why is this happening? It has been said that media coverage underscores the danger that accompanies creative talent, thus softening the jealousy that inevitably arises from their success. It has also been suggested that “wannabes” intentionally cultivate a wild pose to appear more brilliant than they really are, and to get a pass on the mundane responsibilities of life. As they say, any publicity is good publicity. Does all this disclosure result in stigmatization of mental illness or does it trivialize the very real difficulties of those who suffer from such illnesses?

There is an acrimonious and public debate about a potential link between genius and mental illness. At best, the opponents say the research is unempirical; there is usually no control group and there is no universal definition or measurement of either variable (genius or mental illness). At worst, they say it is provides only self-serving “proof” that one researcher’s bi-polar disorder elevates her to the status of genius. In the end, the critics say, the mad genius myth is far too alluring to give up—it is old and glamorous and shimmers with a pseudoscientific patina.

Acceptance and promotion of the mad genius myth is prevalent in the world of outsider art today, so much so that collection criteria reference that belief. The foundation of many European collections is based on the work of artists with mental health issues (e.g., The Gugging Psychiatric Clinic in Austria). Does our response to and assessment of the art change simply because the artist is “mad”?

I struggle with the desire of some, in the world of outsider art, to scrutinize the artist’s biography for proof of authenticity – a diagnosed mental illness – before granting the work special status. The “aura” of mental illness can trump any other identifying characteristics that define an outsider artist. For example, it is generally accepted that an outsider artist must be self-taught. However, a professional artist who succumbs to a mental illness can qualify as an outsider artist. What does this mean? Does the artist forget or relinquish all his or her professional skills? Does the artist gain special abilities and insight by reason only of that illness? Can outsider art be appreciated only by viewers who also have a mental illness? Of course not.

Whether or not one accepts the veracity of the myth, it is accepted as “a given” among many in the outsider art community. I became acutely aware of this point of view at a conference of the European Outsider Art Association in 2013. The Association operates as an umbrella organization for cultural workers devoted to the promotion of marginalized art in Europe. It supports individuals, organizations, or projects that make a significant contribution to reducing the stigma of mental illness, including initiatives that emphasize the dignity of sufferers in a passionate, creative, and innovative way. It appears, however, that artists’ rights are not at the forefront of some undertakings.

Whether or not one accepts the veracity of the myth, it is accepted as “a given” among many in the outsider art community. I became acutely aware of this point of view at a conference of the European Outsider Art Association in 2013. The Association operates as an umbrella organization for cultural workers devoted to the promotion of marginalized art in Europe. It supports individuals, organizations, or projects that make a significant contribution to reducing the stigma of mental illness, including initiatives that emphasize the dignity of sufferers in a passionate, creative, and innovative way. It appears, however, that artists’ rights are not at the forefront of some undertakings.

The connection between mental illness and creativity was the focus of two conference presentations. A Swiss team set out to collect, document, preserve and exhibit the artwork of psychiatric patients. They had approached psychiatric hospitals in Switzerland, asking to see the artwork in files of psychiatric patients. In their view, “the world had a right to see the artwork”. They reported that some institutions had consented to their request, while others had “unjustly” refused. The team did not recognize the ethical (and legal) issues regarding their research. (I was publicly criticized for articulating the confidentiality obligations of the institutions as well as the privacy and ownership rights of the creators.)

Another discussion focussed on the content of the information cards that are displayed with the artwork. It was decided that an artist’s psychiatric diagnosis would be included only if it was necessary to understand the work. There was no discussion about the accuracy of the diagnosis, the sensitive nature of such information, whether the artist had consented, or why such information would be necessary in the first place, unless it were used as an aid to diagnosis. There seemed to be no discomfort about making posthumous diagnoses or breaching patient confidentiality. Nor was there appreciation for the fact that an artist who lives in a psychiatric institution may not have the mental capacity to consent to such disclosure. This discussion raised only concerns and questions for me. As a lay person, why should I distinguish between the artwork of a paranoid schizophrenic and a person with bipolar disorder?

Unless it involves us directly, what is our motivation in labelling someone – a stranger – with a mental illness? Are we complicit to enhance our own status as “normal”? Many argue that mental illness is a cultural and social construct:

To be ‘crazy’ is a social concept; we use social relationships and definitions in order to distinguish mental disturbances. You can say that a man is peculiar, that he behaves in an unexpected way and has funny ideas, and if he happens to live in a little town in France or Switzerland you would say, ‘He is an original fellow, one of the most original inhabitants of that little place’; but if you bring that man into the midst of Harley Street, well, he is plumb crazy (Jung, 1961).

And, as Foucault said, trying to divide madness from reason is itself a form of madness.

Outsider Art 101: the basics

Day 1 of writing was very productive. It was definitely the right decision to take myself away from work-work and unnecessary home chores. Things are good, despite the heavy rains. I decided to go out this morning to buy fire logs instead of chopping down a tree in the forest. I lost my glasses in the process. I am SURE they are somewhere in the gas station, although the staff there denies this. Meanwhile, I’m squinting a lot.

Day 1 of writing was very productive. It was definitely the right decision to take myself away from work-work and unnecessary home chores. Things are good, despite the heavy rains. I decided to go out this morning to buy fire logs instead of chopping down a tree in the forest. I lost my glasses in the process. I am SURE they are somewhere in the gas station, although the staff there denies this. Meanwhile, I’m squinting a lot.

Here is a summary of my writing on “the myth of the mad genius” today. It’s where (I believe) the tangled web of what constitutes outsider art began. More – way more – will follow, including what happened when we changed the terminology from art brut to outsider art.

The concept of the mad genius is deeply embedded in our culture. In reinforcing the stereotype that a life of psychological torture is the price one must pay for creative genius, it trivializes the reality of mental illness and glamorizes the profound truths it can apparently reveal. Nevertheless, the myth has persisted for centuries, despite a dearth of scientific evidence that such a connection exists.

The story of art brut and its link to mental illness begins in the 19th Century. Public “lunatic asylums” were established and radical theories of the unconscious mind were endorsed by Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. More importantly in the history of art brut, the 19th century was the Age of Romanticism, when the savage was noble, the genius was mad, and the hero was a misunderstood outcast. Madness was a metaphor for freedom from the constraints of society; the madman travelled to new planes of reality and was granted special status, being free from social convention and having access to profound truths. While there had been a discussion about the mental state of creative individuals for the past few centuries, they fell short of a diagnosis of clinical insanity. Asylums, where art might be found, opened the door for the study of creativity and madness. To the Romantics, madness was both a piteous and exalted condition and a welcome reprieve from “dreaded normality”.

The story of art brut and its link to mental illness begins in the 19th Century. Public “lunatic asylums” were established and radical theories of the unconscious mind were endorsed by Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. More importantly in the history of art brut, the 19th century was the Age of Romanticism, when the savage was noble, the genius was mad, and the hero was a misunderstood outcast. Madness was a metaphor for freedom from the constraints of society; the madman travelled to new planes of reality and was granted special status, being free from social convention and having access to profound truths. While there had been a discussion about the mental state of creative individuals for the past few centuries, they fell short of a diagnosis of clinical insanity. Asylums, where art might be found, opened the door for the study of creativity and madness. To the Romantics, madness was both a piteous and exalted condition and a welcome reprieve from “dreaded normality”.

The debate about the artist as mad genius typically begins with psychiatrist and criminologist Lombroso who, in 1909, studied the work of his psychiatric patients. He concluded that genius was a type of insanity that caused people to regress to an earlier and savage stage of development; therefore, in his logic, both the madman and the genius were degenerate types. Several years later in 1911, British psychiatrist Hyslop reached the same conclusion, dismissing the “non-art” of the mentally ill as pathological and warning of its degenerate influence. It was accepted that the genius was mad, but the question remained: did the mad themselves create works of genius?

Prinzhorn, a psychiatrist (and art historian) at the University of Heidelberg, argued that his institutionalized patients’ artwork should be studied as the work of individuals, not examined for signs of mental illness. He expanded a collection of art created by his predecessor and published a book in 1922, Bildnerei der Geisteskraken (generally translated as Artistry of the Mentally Ill). He used the term “bildnerei” (image making) as opposed to “kunst” (art) to distinguish his patients’ creative output from the work of artists. Psychiatric patients, he felt, did not have the freedom, self-awareness, or skill of “sane” artists. They did, however, have the ability to see into new worlds, along with children and savages.

Prinzhorn, a psychiatrist (and art historian) at the University of Heidelberg, argued that his institutionalized patients’ artwork should be studied as the work of individuals, not examined for signs of mental illness. He expanded a collection of art created by his predecessor and published a book in 1922, Bildnerei der Geisteskraken (generally translated as Artistry of the Mentally Ill). He used the term “bildnerei” (image making) as opposed to “kunst” (art) to distinguish his patients’ creative output from the work of artists. Psychiatric patients, he felt, did not have the freedom, self-awareness, or skill of “sane” artists. They did, however, have the ability to see into new worlds, along with children and savages.

Artist Max Ernst happened to see the Prinzhorn collection and brought the book back to Paris. Extolling the liberating work of psychiatric patients who took voyages of discovery to the unconscious, the surrealists, led by André Breton, created their own “cult of insanity”. As a way to explore the unconscious mind, they studied dreams and practised automatic writing, activities they believed approximated madness because there was no logic, reason or structure.

French artist, Jean Dubuffet, was a radical member of the surrealist group. He argued against the traditions of art history, where art is studied in the context of its historical development. That art should imitate art was an anathema and such a situation should not be allowed to exist. To Dubuffet, contemporary art was like a parlour game where players must understand a secret language to appreciate the artwork. Society had unwittingly accepted the rules of the game and these rules must be challenged.

Dubuffet had a two-fold agenda: to subvert and expose the emptiness of conventional modern art and to explode the traditional solidarity between artists, critic, and public. In his view, art standards are the result of cultural conditioning and stereotyped opinions where no one dares question the value of a work. We have come to accept that only art that hangs in a museum is worthy of consideration:

… art is the monopoly of the privileged intellectual and the professional artist. … [T]he art system is sustained at the centre by a cultural ideal that is untouchable and inalterable, based as it is on the unshakeable belief in such things as our “cultural heritage”, the legacy of the past, and the fetish of the “great masterpiece” .

Dubuffet asked that we not blindly accept the status quo, but rather, embrace other kinds of art. He asked that we consider this question: what else could art be like?

Dubuffet began to collect art that he believed was unadulterated by culture and mimicked nothing; that is, art that is “raw”. Thus, the term “art brut” (raw art) was coined. Its creation was direct, uninhibited, original, and unique; the creators did not consider themselves to be artists, nor the work they produced to be art. Art brut is visual creation at its purest – a spontaneous psychic flow from brain to surface. His collection began with the work of those far removed from the commercial art world: psychiatric patients, self-taught artists, and isolated individuals.

Dubuffet began to collect art that he believed was unadulterated by culture and mimicked nothing; that is, art that is “raw”. Thus, the term “art brut” (raw art) was coined. Its creation was direct, uninhibited, original, and unique; the creators did not consider themselves to be artists, nor the work they produced to be art. Art brut is visual creation at its purest – a spontaneous psychic flow from brain to surface. His collection began with the work of those far removed from the commercial art world: psychiatric patients, self-taught artists, and isolated individuals.

Dubuffet’s initial description of art brut artists is accepted in many art circles today (a topic that will be explored later in this thesis). Art brut artists draw on their own pure, unrefined, artistic expression to create work that springs from their own obsessive need to express themselves, forcing each one to invent his or her own language and means of expression. The artists do not draw on tradition. In fact, they are quite oblivious to the notion of conveying anything to us and oblivious to the very existence of a public.

Dubuffet’s initial description of art brut artists is accepted in many art circles today (a topic that will be explored later in this thesis). Art brut artists draw on their own pure, unrefined, artistic expression to create work that springs from their own obsessive need to express themselves, forcing each one to invent his or her own language and means of expression. The artists do not draw on tradition. In fact, they are quite oblivious to the notion of conveying anything to us and oblivious to the very existence of a public.

While much of Dubuffet’s art brut collection was made up of work by patients in psychiatric institutions, he argued against the art of the insane. There was no such thing as “the art of the mad anymore than there is an art of people with sick knees” . However, he believed that “madness unburdens a person, giving him wings and helping his clairvoyance… ”.

In general, Dubuffet’s artists were isolated outcasts who created art in unconventional ways. They were unaware of being artists: they had no desire to communicate with an audience and they did not ask to be understood. They were indifferent to any social approbation or commercial gain. In essence, art brut artists were “the un-culture” of the art world. They were “ignorant of any order but their own obsession with image-making”.

In general, Dubuffet’s artists were isolated outcasts who created art in unconventional ways. They were unaware of being artists: they had no desire to communicate with an audience and they did not ask to be understood. They were indifferent to any social approbation or commercial gain. In essence, art brut artists were “the un-culture” of the art world. They were “ignorant of any order but their own obsession with image-making”.

So what of the assertion that madness fosters

artistic genius? Next blog…

Degenerate art

Why do I hear from so many more of you when I write about “life bloopers” than about art? I’m glad you find my personal adventures so amusing… If you’re wondering … the washing machine is working just fine but I am still sleeping on bags of cement 🙂

I was watching a video recently: The Rape of Europa. It is about the staggering amount of art that was looted by the Nazis during the war. I will tell you about this later, but I realized that I hadn’t told you about an exhibit I saw last May in New York, called Degenerate Art: the attack on modern art in Nazi Germany.

While some 19th Century psychiatrists (like Prinzhorn) took a particular interest in the art of their patients, others like Lombroso, declared the art of his patients indicated a return to an earlier stage of human development. British psychiatrist Hyslop declared the “non-art” of the mentally ill as pathological, having a degenerate influence. The most extreme act of blocking the so-called degenerative influence of art took place during the Nazi regime, when there was a move to remove modern artists and curators from their positions in the art world. All degenerate and decadent art was removed from galleries and museums; many modern artists disappeared and were presumed to have been exterminated. Thousands of artworks were destroyed and interest in new and alternative art forms was squashed.

A “degenerative art exhibition”, put together by the Nazis in 1937, displayed the work of modern artists (like Picasso) and Prinzhorn’s collection of work by his psychiatric patients. Degenerate art was deemed to be deplorable because it did not represent all that was good about Germans and Nazi Germany. Side-by-side with the degenerate works were examples of “good art”, that is art that complied with the Nazi agenda, such as the example above. It shows pure women, perfect examples of the Aryan race.

The exhibit in New York brought together some examples from the 1937 Nazi exhibit. During that regime, art was intended to strengthen the Third Reich and purify the nation. Artistic expression was yet another way to further political aims: art was propaganda to shape the German population’s attitude about what was right and pure. According to Hitler, the purpose of art was to glorify the perfection of the Aryan race. European modern art had absolutely no place in the German art world.

Take Nolde, for example. He supported the Nazi party from the 1920s and his artwork was greatly admired by many Germans, including Goebbels. When Hitler declared all forms of modern art as “degenerate”, the Nazi party officially condemned Nolde’s work. Over 1,000 of his paintings were removed from museums (more than any other artist) and his work was included in the 1937 Nazi Degenerate Art exhibit. His appeal to the Nazi regime was dismissed. He was prohibited from painting, even in private. (He did, however, paint some watercolours, which he hid.)

Take Nolde, for example. He supported the Nazi party from the 1920s and his artwork was greatly admired by many Germans, including Goebbels. When Hitler declared all forms of modern art as “degenerate”, the Nazi party officially condemned Nolde’s work. Over 1,000 of his paintings were removed from museums (more than any other artist) and his work was included in the 1937 Nazi Degenerate Art exhibit. His appeal to the Nazi regime was dismissed. He was prohibited from painting, even in private. (He did, however, paint some watercolours, which he hid.)

The New York exhibit was both fascinating and repugnant. Those we have come to know as the masters of modern art were once denigrated and despised. What I didn’t see on exhibit were the works of art brut (outsider) artists. I know that such works were also exhibited as the work of “insane” artists, along with examples of modern art. The point was this: “modern artists are as crazy as patients from psychiatric institutions”.

Ever the curious (and intrepid) art tourist, I tracked down a curator and asked about the omission. The curator confessed to having no knowledge of the work of art brut artists being on display at the original Nazi exhibit in 1937. Too bad. The New York exhibit would have been sensational if it had told the full story.

Art from Angola Prison

I just returned from a trip to New Orleans – the first time being away from home on Christmas and the first time bar-hopping with my son, but that’s another story. Because this blog is about outsider art, not intoxicants, I will refrain from telling you about Bourbon Street, and the copious amount of alcohol that is consumed there. Let’s just say it’s a party every day in New Orleans…

I just returned from a trip to New Orleans – the first time being away from home on Christmas and the first time bar-hopping with my son, but that’s another story. Because this blog is about outsider art, not intoxicants, I will refrain from telling you about Bourbon Street, and the copious amount of alcohol that is consumed there. Let’s just say it’s a party every day in New Orleans…

Prospect 3: Notes for Now (called “P3”) is an international contemporary art biennial on now at 18 different venues in New Orleans. I attended the exhibit at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, which included the work of Basquiat, The Gasperi Collection: Self-taught, Outsider and Visionary Art, and a particularly interesting exhibit about the prisoners in Angola. I am compelled to describe the prison art collection first: Keith Calhoun & Chandra McCormick: Slavery, The Prison Industrial Complex. For those of you who live outside the USA, Angola is the state penitentiary in Louisiana. It is a maximum security institution, housing over 6,000 prisoners and 1,800 staff members. In short, it is a small city unto itself where the last stop on the bus is death row and Louisiana’s execution chamber. (The United States is the only developed country that retains this abhorrent practice.)

The Calhoun and McCormick collection focuses on the lives of Angola’s prisoners and the impact of incarceration on their families. Because this specific exhibit was about art and justice, it was impossible for me to view it wearing anything but my “lawyer hat” and I left the exhibit railing against the absence of justice in far too many cases . The purpose of the images was to “restore humanity to a marginalized population”. It aimed to chronicle the daily life of an African-American within the prison system in Louisiana. The problem is this: to chronicle the lives of African-American prisoners is to normalize it and that, in itself, is an injustice. While roughly 12 – 13% of the American population is African-American, they make up 40% of the male prison inmates in jail or prison in the USA. Forty percent.

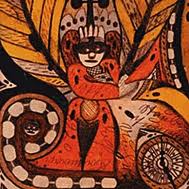

There are many innocent people in prison and how they got there is often the result of racial stereotyping and lack of legal representation. And, indeed, the profile on Welmon Sharlhorne was a prime example of how the system does not work. (Artwork pictured at top of page.)

Sharlhorne was born in Louisiana in 1952. He was convicted of robbery when he was 14 and went to juvenile detention for 4 years. Upon his release, he worked independently mowing lawns in the affluent areas of New Orleans. He soon got into a dispute with a customer about the amount of money he had earned; he was charged with extortion and assigned a public defender. His lawyer suggested a plea bargain sentence of 3 years. Welmon refused and fired his lawyer. Representing himself in court, he was convicted and sentenced to 22 years at Angola prison.

Sharlhorne was born in Louisiana in 1952. He was convicted of robbery when he was 14 and went to juvenile detention for 4 years. Upon his release, he worked independently mowing lawns in the affluent areas of New Orleans. He soon got into a dispute with a customer about the amount of money he had earned; he was charged with extortion and assigned a public defender. His lawyer suggested a plea bargain sentence of 3 years. Welmon refused and fired his lawyer. Representing himself in court, he was convicted and sentenced to 22 years at Angola prison.

Sharlhorne began drawing in prison, believing that his art and God saved him during his long years of incarceration. He obtained envelopes and a pen in order to write to his (non-existent) lawyer and used tongue depressors as a straight edge for his drawings. A clock appears in each of his drawings as a reminder that by taking time to commit any crime, little or big, it is time out of your precious time of freedom.

Herbert Singleton was another artist from Angola prison. His painted wood bas relief (at left) shows the fate of an African-American involved in the justice system. It ends with his execution. The captions says it all: LAWDIHAVEMERCY.

(from the Gordon W. Bailey collection)

Our Faith Affirmed – Works from the Gordon W. Bailey Collection

Our Faith Affirmed is a current exhibit at the University of Mississippi Museum of Art. On exhibit are the works of 27 African American self-taught artists born between 1900 and 1959, including Thornton Dial Sr., Roy Ferdinand, Bessie Harvey, Lonnie Holley, Charlie Lucas, Jimmy Lee Sudduth, and Purvis Young. I am familiar with the work of these artists from my readings, but growing up far away in Canada (both in distance and culture), I have no first-hand knowledge of their lives. I know that the vast majority of my international readers will agree that we have a lot to learn about this particular genre and even more to learn about America’s Southern culture, both past and present.

Our Faith Affirmed is a current exhibit at the University of Mississippi Museum of Art. On exhibit are the works of 27 African American self-taught artists born between 1900 and 1959, including Thornton Dial Sr., Roy Ferdinand, Bessie Harvey, Lonnie Holley, Charlie Lucas, Jimmy Lee Sudduth, and Purvis Young. I am familiar with the work of these artists from my readings, but growing up far away in Canada (both in distance and culture), I have no first-hand knowledge of their lives. I know that the vast majority of my international readers will agree that we have a lot to learn about this particular genre and even more to learn about America’s Southern culture, both past and present.

Recently, I had the good fortune to converse with scholar/collector Gordon W. Bailey through my blog. Mr. Bailey organized and curated the exhibition and has an extensive collection of work by African American self-taught artists. He kindly forwarded a catalogue of Our Faith Affirmed to me.

In his catalogue essay, UM alumnus, and now acclaimed rapper, Jason “PyInfamous” Thompson, wrote that the artists’ works are not traditional because “no artist – no person – that has endured the sweltering, seething heat of Southern segregation and sectarianism can be considered ‘traditional.’ In a land where tradition included nooses and nihilism, there was a necessity to express the anxiety and anguish that came with being Black in the South.”

My own studies have focused on how we define “outsider” art. As I settle in to write my thesis on this very topic, I can tell you that there is no single definition that we all agree on. Some writers focus on the self-taught aspect of the work; others point to the marginality of the artists; while others consider an artist’s biography as the most important indicator of being outside – or inside (outside or inside of what?). Unfortunately, the ball of entwined definitions is still very tangled and I can only hope to shed some light on why we defend our own views with such tenacity.

The artists in this exhibit, states the catalogue, are unique individuals who have unique iconographies, but share context. That context is, of course, the “otherness” of poverty, racism, and segregation. And, I think, that distinguishes the art of Southern self-taught artists from everything else. They have a shared language because they have a shared history. Roger Cardinal described art brut (outsider art) as a “teaming archipelago rather than a continent crossed by disputed borders. The only connection between each ‘island of sensibility’ is that they are all distinct from the cultural mainland. The only likeness is within the work of a single artist.” I would suggest, however, that most Southern self-taught artists live on the same continent.

Take, for example, Roy Ferdinand’s Sulton Rogers Portrait and Charles Gillam’s carving of Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong. They celebrate two great African American men from their respective communities. Jimmy Lee Sudduth’s Cotton Wagon expresses the back-breaking work of cotton pickers he undoubtedly knew, disconnected from each other, bent with exhaustion. Joe Light’s Colored Hobo asks us to consider the fate of one African American man – a homeless vagabond. Even the breathtaking canvases of Thornton Dial, whose work trumps those of the very best abstract expressionists, express more than meets the eye: they speak to American history and politics, particularly racism, and bigotry.

Take, for example, Roy Ferdinand’s Sulton Rogers Portrait and Charles Gillam’s carving of Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong. They celebrate two great African American men from their respective communities. Jimmy Lee Sudduth’s Cotton Wagon expresses the back-breaking work of cotton pickers he undoubtedly knew, disconnected from each other, bent with exhaustion. Joe Light’s Colored Hobo asks us to consider the fate of one African American man – a homeless vagabond. Even the breathtaking canvases of Thornton Dial, whose work trumps those of the very best abstract expressionists, express more than meets the eye: they speak to American history and politics, particularly racism, and bigotry.

The works in this exhibit take us far beyond “self-taught” art that we know in the bigger world of outsider art. These are not fantasy images, they are real and they spring from personal experience. If you have an opportunity to do so, see the exhibit (which runs until August 8, 2015) or browse through the catalogue and reflect on the sobering messages beyond the images. They highlight issues that are still relevant today.

(All images provided courtesy of the Gordon W. Bailey Collection)

In reference to nothing, and everything

Sometimes it is worth writing something down, even if it references nothing in particular. Chances are that it will reference just about everything, or you wouldn’t have paused to think about it.

I just learned about Kintsugi, the Japanese art of fixing broken pottery with gold seams. Wiki tells me that it is akin to the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which embraces the imperfect or flawed. Rather than trying to disguise the repair, it becomes part of the object’s history. Some say that the object is reborn. Others say that its history makes it more beautiful.

This is good news, indeed, for those of us with hearts and souls held together with sticky tape and twine. Never again let us think we are less than perfect.

Anthony Stevens (again)

I have introduced you to UK textile artist, Anthony Stevens, in earlier posts. I am a big fan of his work, even though it diverts me from my path of art discoveries in Canada. It is worth the diversion.

It seems that I am not the only one who admires Anthony’s work – he has been invited to exhibit so much lately, that it would make “professional” artists green with envy. His first big exhibit was in London this past summer (2014), called Prick Your Finger. Here is a link to some photos from that exhibit.

Anthony was invited to exhibit in Frankfurt in September at a group show and micro-residency called Raw Threads. Anthony has written a wonderful piece about the show and it’s worth taking the time to read it. (If you don’t have time to read it, he had a blast and enjoyed the companionship of fellow fabric artists.)

Anthony was also invited to exhibit at a fair in Brighton (UK) in September, with an organization called Outside In. It’s the biggest annual arts show in SE England only a select number of artists were invited to exhibit. And, as if that weren’t enough, he is in a group show next year in London at St. Pancras Hospital Gallery. It’s organized by Sue Kreitzman and will feature textile artists. The world of outsider art is small. You will remember that I wrote about Sue Kreitzman a few months ago. I met her at the Outsider Art Fair in NYC in May and blogged about the incredible universe of art she has created.

All of this is to say that if you haven’t checked out Anthony Stevens yet, now is the time. Contact him at Outside In and buy something before you can’t afford it. Don’t say I didn’t tell you.

In memoriam: Ian McKay (1949 – 2014)

Sadly, Vancouver artist, Ian McKay, has passed on. He could only be described as “larger than life.” He started out as a mime artist and never lost his flair for the theatrical: full of life, quick to laugh, a friend to many. If you ever met Ian (and because he told everyone), you would know that he was the opening act for a Led Zeppelin concert and performed with Cheech and Chong at the burlesque house, The Shanghai Junk. Around that time he took a fundamental art course, but found it too academic (and boring). Instead, he taught himself to draw by studying the old masters. This soon led to his first painting exhibit in Toronto in 1972.

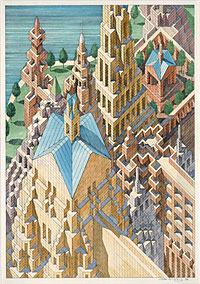

Ian was a prolific painter, but the quirky brilliance of his work was the Tower of Babel project. Although Ian developed macular degeneration, which left him legally blind, he hand-drew these works (with a large magnifying glass) until the very end. This is how Ian described his fantastical, imaginary drawing project he called “Axonometropolis”.

Axonometropolis is a city of the imagination; infinite in structures, roads, canals and bridges as if in a daydream.

I have been working on The Babel Project for twenty years. I was inspired by the writings of the blind author Jorge Luis Borges. Ironically perhaps, like him, I am nearly blind.

When inventing the Library of Babel, Borges said that the universe is a sphere whose centre is everywhere and circumference nowhere. I am imagining the City of Babel. Babel was to be constructed to reach Heaven; and so, for me, it must be built to infinite scale.

Axonometropolis is a term I invented to describe a city which can only exist as an axonometric drawing, which describes mass, volume and spatial relationship without perspective. Therefore, there are no vanishing points or horizon. The buildings, pathways, lakes and gardens are visible in their actual scale, in all directions, to infinity.Until 2010 I was drawing only the “districts” of Babel. Now the districts are expanding into each other, forming larger areas where the viewer can get a greater sense of my ultimate goal.

Because I am nearly blind, I can only create one small area at a time, using a magnifier. The drawings started in 2008 are improvised directly, in ink, freehand without a plan.

Ian’s work did not go unnoticed. His drawings were included in a beautiful book, Visionary Architecture: Unbuilt Works of the Imagination (1999, Ernest Burden, McGraw-Hill). He was one of the amazing artists included in this book, which featured the famous 18th Century architect, Giovanni Piranese. Marion Harris exhibited his work at the Outsider Art Fair in NYC. In 1992, he received the award of excellence in international competition from the American Society of Architectural Perspectivists. He was also a member of the Blind Artist’s Society.

You had quite a journey, Ian McKay. You were a good friend to many, and always put their needs before your own. I will always remember you sitting in a corner of your neighbourhood restaurant, the Whip, glass of wine and cigarettes at hand. Maybe you are now resting, old friend, in a snug corner of one of your own drawings, telling tales of your grand adventures. You will always be with us.